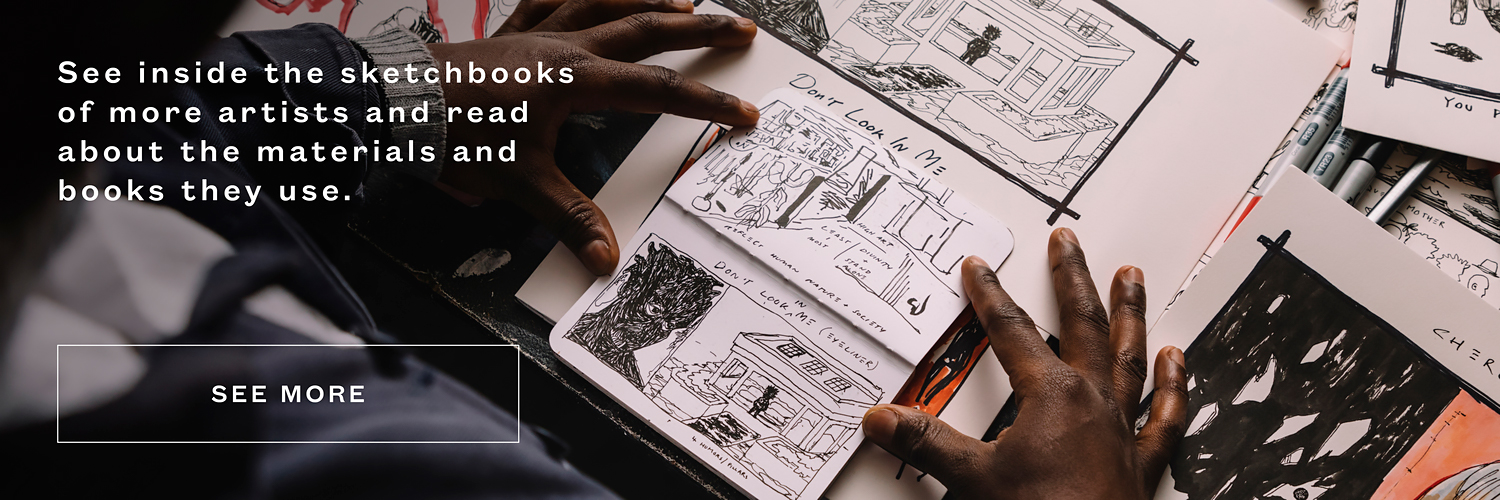

Ranny Macdonald is a London-based artist and musician whose practice is deeply rooted in drawing. In this article, he describes the important role sketching plays for him, and how rapid, intuitive mark making in his sketchbook allows him to capture fleeting moments and elusive ideas. Whether it’s the quickly shifting light and colour of a scene, a moment caught within the briskness of urban life, or creative concepts competing for dominance in his imagination, this spontaneous sketchbook process allows him to record ideas in their rawest form – ultimately shaping the distinct perspective of his work.

Inside the Sketchbook of Ranny Macdonald

Drawing is at the heart of everything I do (artistically speaking!), and for as long as I can remember, it has been a beloved companion and a space I feel totally safe within. Despite this, and the fact that I try to carry a sketchbook everywhere I can, I’ve never thought of myself as a sketchbook person. You might know the type I mean, the kind of artist who might be in your A-level class or art school, whose shoulder you can gaze over in awe as they flick through endless colourful double spreads. I don’t know what these people have, but I certainly don’t have it.

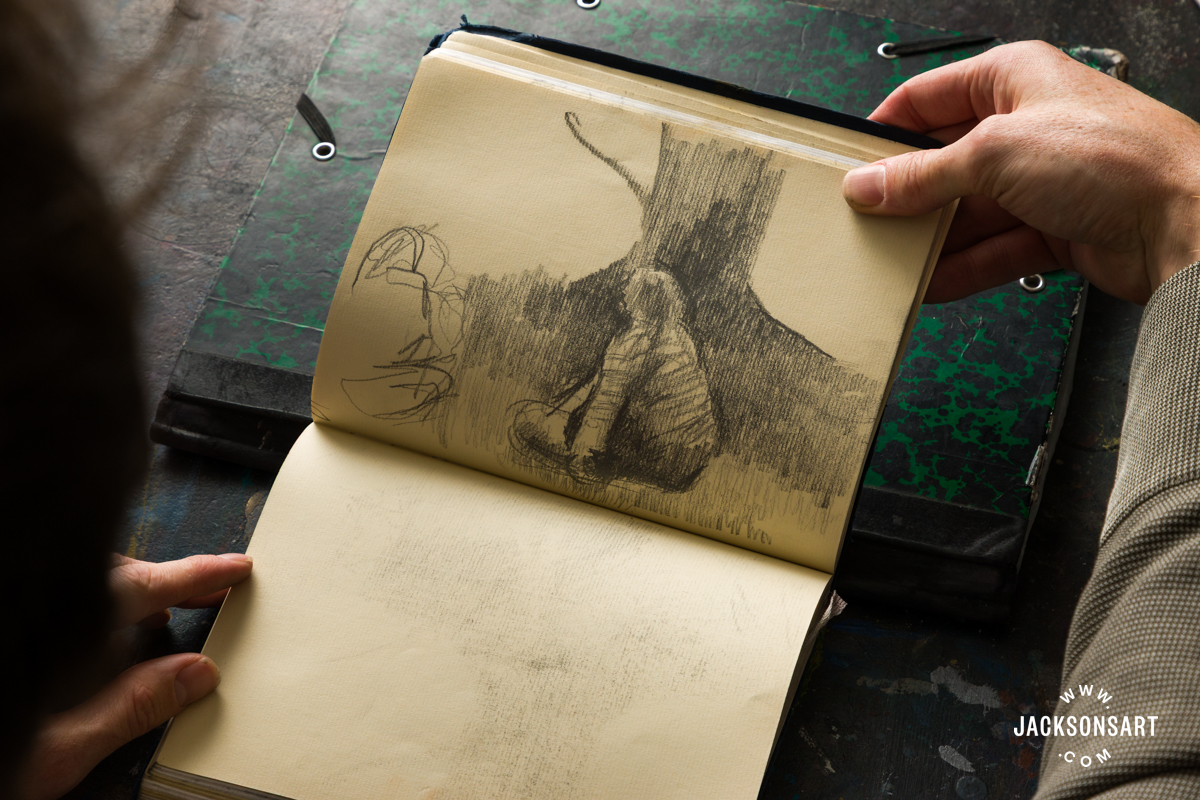

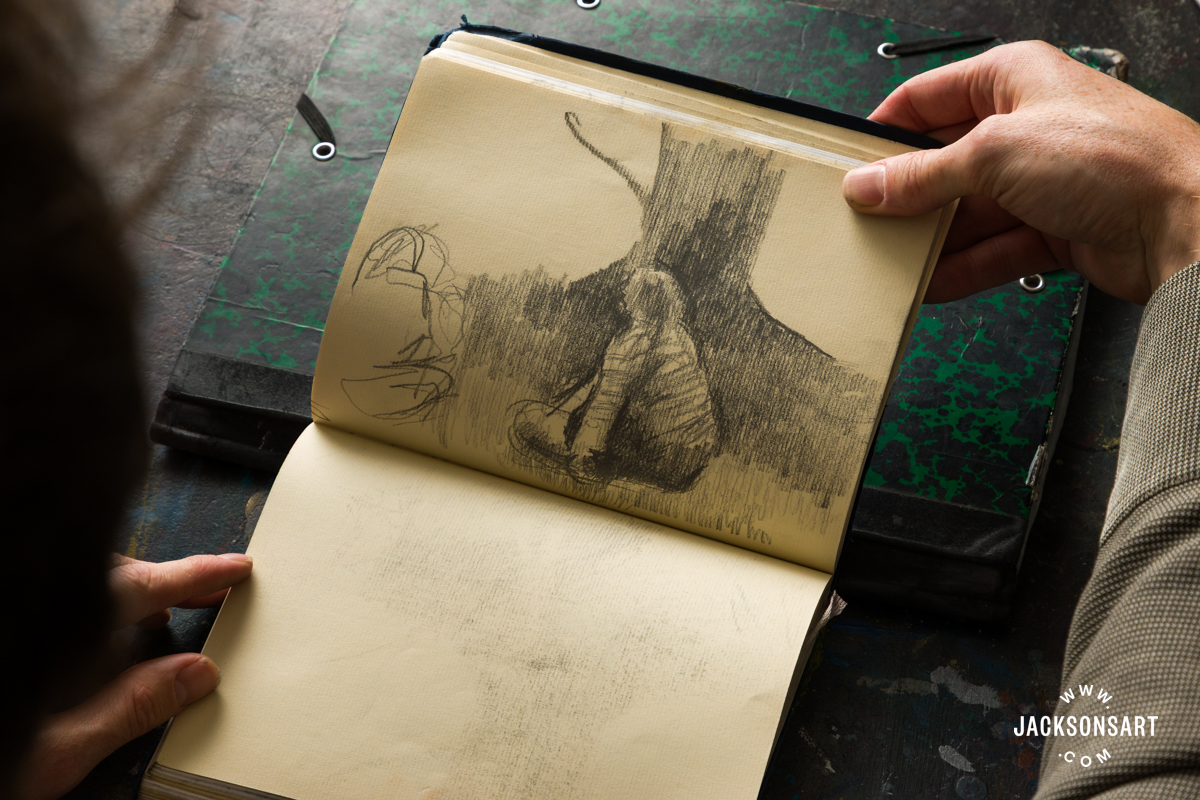

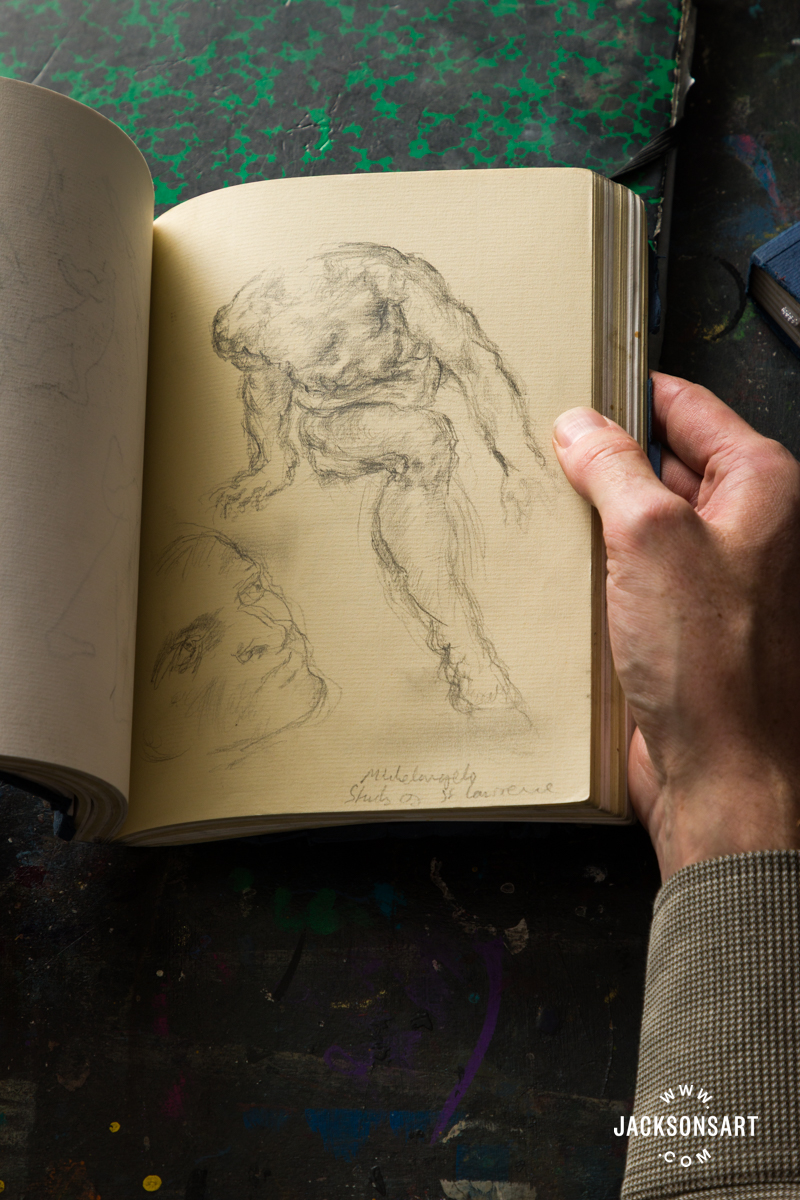

My sketchbook practice has always been a bit more on the functional side – a place where drawing isn’t about making anything that looks good or beautiful, or that would even necessarily make sense to a lot of people. I think you could loosely sum it up as a place of exchange between the physical world and the world of ideas. This works like a two way street, a kind of threshold that both can pass through, and translate into the other. The physical, observed world is turned into ideas – like marks and compositions – but also where an idea, something you lie in wait for and happen to glimpse whilst on the bus, can be worked back through into the physical world.

I love this process particularly because it feels so functional. There’s nothing flowery or ornamental about it at all. I’m always waiting for that glimpse of an idea, and when it does come – it might be a form, a figure in a kind of space – it feels half-dark, a delicate cloud that might dissolve if I tried to touch it. Drawing in my sketchbook works as a kind of conduit in that moment, but it is often fraught and ends up slipping away, and often it can feel like wrestling (not that I’ve done a whole lot of wrestling).

Since studying on The Drawing Year at the Royal Drawing School in 2021, I’ve had quite a consistent formula. I have a book for monochrome and quick drawing, and a setup for colour, for which I use chalk pastels.

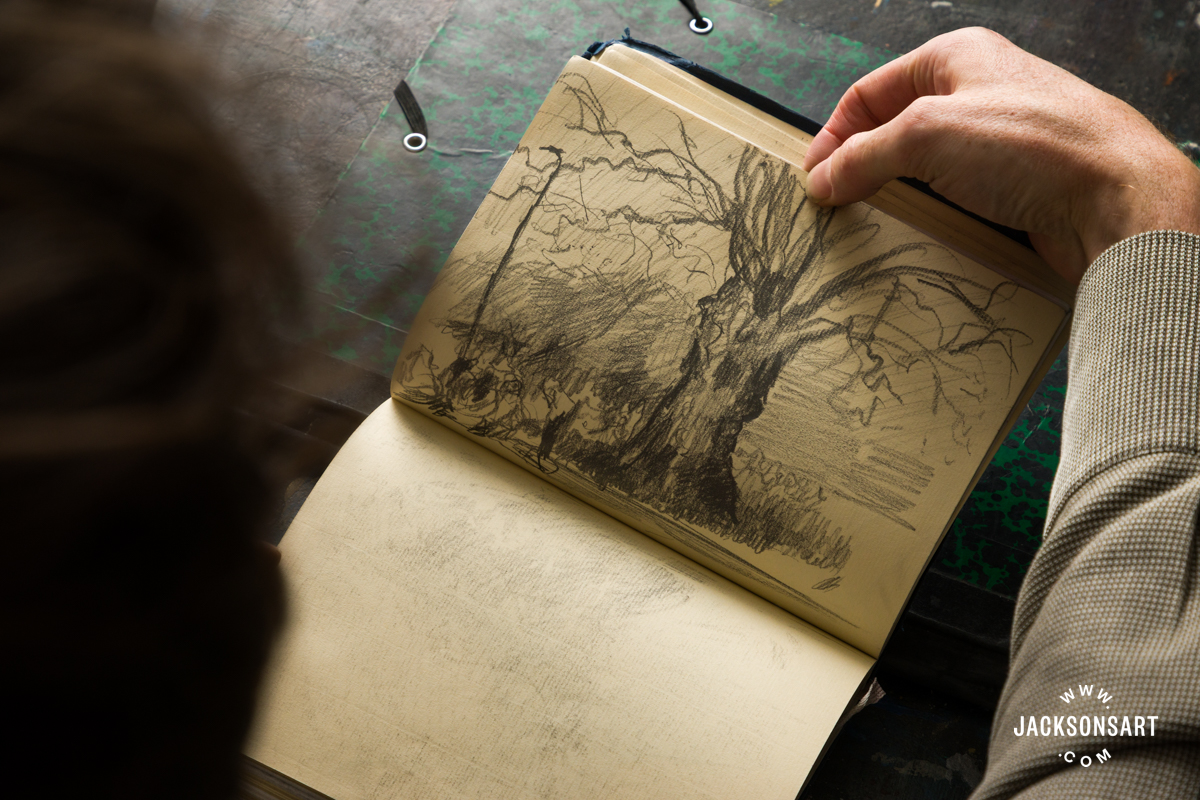

For the monochrome quickness, I really like the square Fabriano Artist Journals, for two reasons: they’re light and have a lot of paper, so I don’t feel precious, which is really important, and they have a mix of white and brown paper, which keeps you on your toes. I try to carry this kind of book around as much as possible (although maybe not as much as I should).

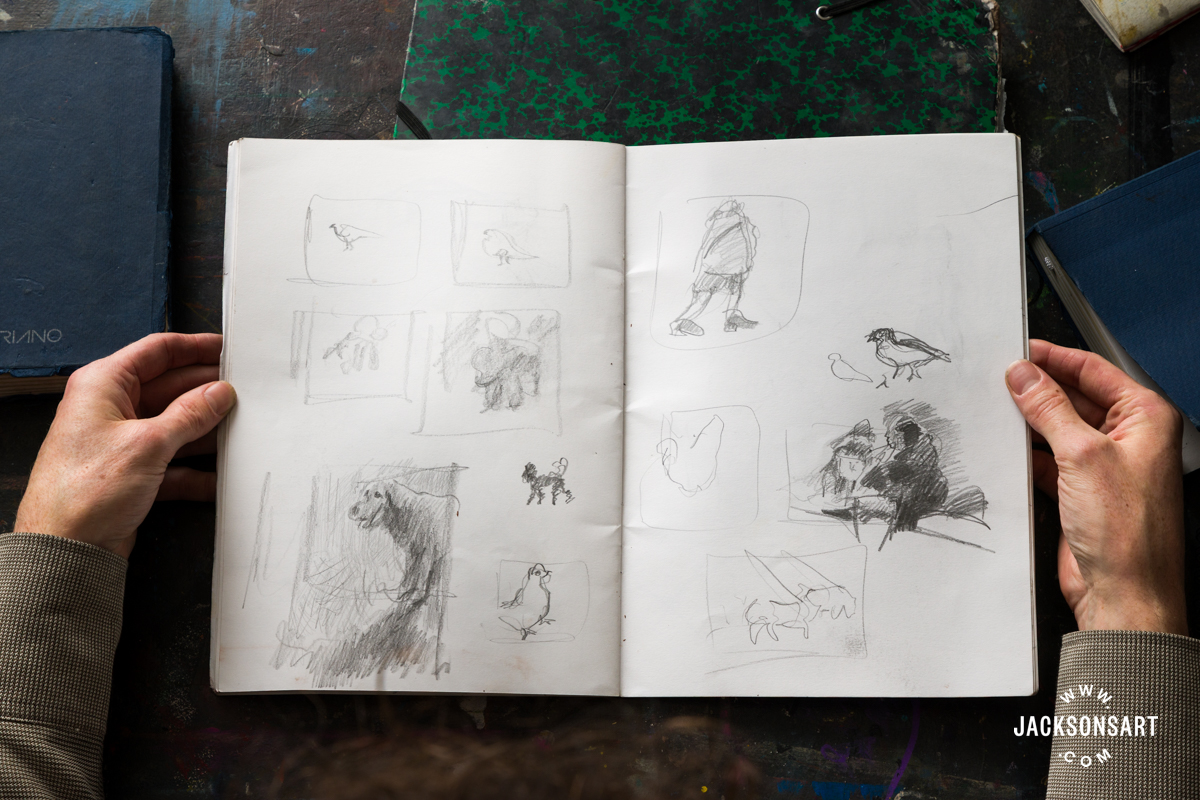

There are two places I mainly use my sketchbook: out and about to quickly observe and capture things for my bigger studio works, and also in the studio to rattle off multiple versions of painting ideas to try and work out the composition. This is usually a bit of a frenzy. I get a spark of an idea and have to push to find it. Each one of these might take anywhere from 30 seconds to 10 minutes.

I sometimes use loose sheets as well, but in those moments, I don’t want to think about anything else. I might need to do multiple quick versions, and not having to think where the paper is and just flicking over the page helps me keep in that state of searching through drawing. Also, it’s great to have them all in one place to look through.

My current way of working with chalk pastels evolved out of using coloured pencils which I started with a few years ago. I really learnt about colour from my Grandma, Jane, who has been a watercolour teacher and painter since she learnt in her mid-30s. In between studies, working with her was the first time I got to know the different pigments and colours, and through her teaching, I began to see colour as a kind of language that you could use intentionally.

It was truly mind blowing actually, I felt like a whole new world had opened up and I was keen to practice it more and more. I did use watercolour out and about, but it was quite impractical, and I was in a kind of space where I liked to work everywhere, so I switched to coloured pencils. I used them a lot at this time in sketchbooks.

The Faber-Castell oily ones are a little more expensive but you don’t need many of them, and can add to them slowly, subbing new ones in to try out palettes. They are great as the pigments are strong and they can be layered and mixed like paint. I’d intentionally pick ones that related to paints I’d learnt about in watercolour, so I could get to know them better.

I think it’s important to get to know colours, not just ones you like, but what relationships colours form with each other and how they work together in groups. Then making a picture becomes like hosting a party, ‘these two get on like a house on fire … these two can’t be in the same room … this one’s a bit wild, etc’.

The other thing I did back then was to work in sketchbooks but make a little rectangle on the page to work inside. Its a great way, if like me, you find the whole page overwhelming, of being able to use the edges and practice making compositions. Would recommend that to anyone making pictures!

The pencils I had been using were just too slow to build up layers, but the chalks have a fluidity to them, and you can cover a lot of paper quickly with smudging them. So they work well for this – the colours and their matt finish and softness were also things I was drawn to. There were quite a few people in our year using them and getting into them at the time.

One thing that I found was a bit of a game-changer was to work on primed paper. So, I would prime with gesso and a colour, meaning I’d have something to work against that isn’t a white space. It meant that capturing a fleeting light could become possible as the page was built into your work without having to do anything.

My advice for anyone getting into art and drawing is to practice being open – you never know when inspiration might strike, and you have to get it down as soon as you can. I think the more you work on the connection between your eye and your hand, the easier and more fluent it gets. In my work, everything comes from observation. First you look, then you see, and then you can have a vision!

Materials

Conté à Paris charcoal pencils

Fabriano Artist Journal 12 x 16 cm

About Ranny Macdonald

Ranny Macdonald is an artist and musician working in London. His work takes on the often-neglected perspective of urban creatures, such as dogs, cats, and pigeons, as well as surreal still lifes where objects take on unique personalities. Using materials such as pastels, pigments, and distemper, he explores our relationship with the natural world through an imagined non-human lens. Ranny is a graduate of Slade School of Fine Art, City and Guilds Of London Art School, and most recently, the Royal Drawing School’s postgraduate programme. He has exhibited nationally and internationally, and in 2023 he was selected for Bloomberg New Contemporaries.

Further Reading

Everything You Need to Know About Pastel Paper

Using Soft Pastels for Observational Drawing

The Dark History of the Pencil

Shop Sketchbooks on jacksonsart.com

The post Inside the Sketchbook of Ranny Macdonald appeared first on Jackson's Art Blog.

Trending Products